Tucked into the Glass Case Collection of books at the Taranaki Research Centre at Puke Ariki is a copy of He korero tipuna pakeha no mua, ko Ropitini Kuruho, tona ingoa, the first book of illustrated colonial fiction translated into Māori, published in 1852. The life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe was originally written by Englishman Daniel Defoe (1661?-1731) and published in 1719.

Why was the Māori edition published, and how did this copy come to be held by the Taranaki Research Collection?

This is the story behind the book.

Defoe’s novel is considered by some to be the first example of English realistic fiction, and some say it is only second to the Bible in the number of languages it has been translated into. There have been so many adaptations of the story that it is considered a genre of its own, known as Robinsonade. The story is narrated by the fictional character, Robinson Crusoe, with the first edition having Robinson Crusoe even credited as the author, so many readers thought the story was a true travelogue. It was so popular it went through four editions in its first year.

A key adventure in the story is that Crusoe, an Englishman shipwrecked on an island, rescues a Caribbean slave from a cannibal tribe. “Friday”, as Crusoe named him, converts to Christianity and becomes Crusoe’s friend and servant. As such, the story can be seen as a story reflecting a cultural mind-set of a “civilised” European and a “savage” who is redeemed by assimilation into the European culture.

The 20th Century Irish novelist and literary critic James Joyce famously described Crusoe as “the true prototype of the British colonist. ... The whole Anglo-Saxon spirit in Crusoe: the manly independence, the unconscious cruelty, the persistence, the slow yet efficient intelligence, the sexual apathy, the calculating taciturnity."

The first line of the preface of the Māori translation states that the “The life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe are too generally known to require any comment.” Defoe’s work had been well received initially, but it reached a bigger cult status during the later Victorian period. Assoc Prof Shef Rogers says that by time of the 19th Century translation, Crusoe had become a “symbol of the rugged [colonial] individualist amid the natives,” well known to both children and adults alike. Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress also had similar status in English culture at the time, making both titles an obvious choice for translation by the colonial government of the time.

One of the first attempts to write down te reo Māori was made in 1815 by one of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) team led by Samuel Marsden: Thomas Kendall (1778?-1832), who printed and published in Sydney under the title, A korao [korero] no New Zealand, or, the New Zealander’s first book. Kendall was enthusiastic but not a trained linguist, so after criticism of this work from the CMS in England, Kendall took Ngāpuhi chief Hongi Hika and Hika’s relative Waikato of Rangihoua to visit the world-renowned linguist Samuel Lee in Cambridge, England.

Initially Lee transcribed their speech using the full English alphabet but quickly realised he could simplify it by dropping 13 of the letters. Following this, in 1820, Kendall published A grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand, containing the best orthographic (writing conventions) of the Māori language of the time. This was tested, tweaked and enlarged by other Church Missionary Society members in New Zealand.

The second edition of William Williams Māori dictionary was the first to use the 'wh' convention published in 1852. Ropitini Kuruho was released the same year and used this new convention. (Macrons were to come much later.) By the 1850s, about half the adult Māori population could read their own language, and a third could both read and write.

Early missionaries were amazed at how enthusiastically Māori took up reading and writing in their own language from the 1830s. Novelty, status, the association with the new religion, curiosity about the new European world plus the increasing importance of the land purchase documents fed into this.

‘A Subscriber’ to the Wellington Independent in 1849 (21 July, p.2) described Māori as “fast readers”, “now quite capable of understanding and appreciating the value of a publication” such as the proposed Māori language newspaper. According to C J Parr’s survey of early Māori literacy, “by 1840 in almost every North Island village, coastal and inland, some Maoris, many of whom had never seen a [European] missionary, could read and write.” Until the mid-1850s, literacy rates amongst Māori were higher than that of the English colonists. They were keen to acquire publications and embraced letter writing. Their tradition of spoken storytelling meant that books would often be read aloud to a group. Colonists were amazed at the large sections of publications that Māori were able to recite from memory and the quality of their questions and discussion of the content.

Some of the earliest places children were taught to read and write in Māori were missionary schools, and one of the earliest examples of these was at what is now known as Kemp House, in Kerikeri, started in 1823 by James Kemp – another of the Marsden CMS team. In Pākehā society at the time, it was much more common in England for boys to be educated (if at all) than girls, so it is surprising that the Kemp school also included a class for girls and infants, taught by Charlotte Kemp and their neighbour Martha Clarke. Their students tended to be high-born daughters of Rangatira who often boarded with the Kemp family. The Pākehā community was tiny - education was primarily in Māori.

This was also the home where Henry Tacy Kemp, the translator of Robinson Crusoe, was born in 1821. Unsurprisingly he grew up as a fluent speaker in both Māori (particularly the Ngāpuhi dialect) and English, leading to him becoming regarded as one of the best and fastest translators of his time.

This bilingualism led to work that hinged on interpretation skills. He was made an Officer of the Government on the 6 February 1840, and one of his first pieces of work was a translation of the Treaty of Waitangi that was sent to London. He held various government roles, such as Native Secretary and was involved in negotiating land sales.

Most of the publications available in Māori in 1852 were religious texts, particularly bibles and a few clearly non-fiction titles. The texts that Kemp was involved in producing, including the translation of the two fictional works Robinson Crusoe and Pilgrim’s Progress, aided the government policy of acculturation. Nonetheless his translation did not just reflect fluency: Dr Godfrey Pohatu described Kemp’s 1852 translation of Crusoe to Rogers from a 20th Century perspective as “exceptionally beautiful”.

Ropitini Kuruho is believed to be the first illustrated book in Māori. The lithographed pictures were produced by Dr Thomas Shearman Ralph (1813-1892), who lived in Wellington from 1851-57. He produced some of the first etchings and lithographs in the city at that time.

Ralph had trained as a medical doctor, a common background for scientists of the period, and is best known for his botanical interests. Ralph published a number of botanical works, including one about Wellington tree ferns - perhaps explaining the attention to detail in the palm-like vegetation depicted in the frontispiece.

He was the second secretary of the New Zealand Society (NZS) in 1852, the first being Walter Mantell. Governor George Grey was the President of the NZS at this time (1851-53). This evolved into what is now known as the Royal Society of New Zealand.

Say ‘Crusoe’ and the image of a man on a tropical island that you imagine is unlikely to be heavily clad in animal skins and a shaggy hat, but that was the common image at the time of publication and portrayed by Ralph. For example, the photograph of the early New Plymouth surveyor Thomas Kingswell Skinner (1849-1925) in a fancy dress costume depicting Robinson Crusoe is in a similar hairy style.

The English title page states: ‘Translated into the New Zealand language under the direction of the Government’, Grey had authorised its translation and printing. The government did not have an in-house printer until 1865, before then printing work was contracted out. One of the two Wellington newspapers, The Independent, won the Ropitini Kuruho tender.

It was published as a paperback, some with pink and some in blue covers. A few wealthier owners would have had their copies bound in hardback to order, the wealthiest perhaps opting for a binding that matched the rest of the books in their personal libraries.

The book had two title pages: the first in English opposite a frontispiece illustration and the second “translated into the New Zealand Language”, in other words, Māori. This format is known as ‘parallel title pages’. The only other English text in the entire text is the preface, by “H Tacy Kemp, Native Secretary.” The abridged story is 157 pages long.

An edition of 1000 copies released in April 1852 was reviewed in The Independent on the 29th of May 1852. Given they had printed the book, it is unsurprising that the review was extremely favourable, including high praise of those involved in the production, including their own typographical excellence! Confident that “the manner in which the story is told, corresponds entirely with the manner in which the Maories themselves are in the habit of relating events of any great importance”, the reviewer believed this would help to implant a taste for reading, expressing the assumption that Māori were as in need of developing this habit as the un-educated adults of the European population. They state:

“Only 1,000 copies of this work have been published, but if we are not greatly mistaken, another and a larger edition will soon be required. We understand it is the intention of the Government to sell the work at a cost which will cover the expenses of its publication, and this we think is the best and most prudent course they could adopt. The Maori no more than the white-man begrudges the cost of a thing he prizes, the cost of a horse does not prevent him obtaining it, though it may give it in his eye more than even its proper value, so will it be with this edition of Robinson Crusoe, he will in all likelihood value it the more from having had to purchase it. The illustrations with which it is adorned will, at the time it aids its usefulness, add to its value. Pictures are alike objects of interest and pleasure to the tutored and untutored man, but to the latter they convey to the mind a kind of instruction which nothing else can so well accomplish.”

Of the newspapers currently digitised on the PapersPast database, only one other newspaper, also in Wellington and aimed at English speakers reviewed the publication, just a few days later. The New Zealand Spectator & Cook Strait Guardian had a reputation for ingratiating itself with Grey it lives up to with a similarly glowing review, despite its competition with The Independent. Unsurprisingly, the printer is not named, but the skills of Kemp, Ralph and Grey are. It acknowledges the Māori fondness for reading, and says that:

“The experiment of enlarging the field of their reading by translating into their language standard English works adapted to their peculiar tastes has been attempted with complete success; the book now before us has been received by the natives with intense interest, and in proof of this, and of the sound judgment with which the selection of this work has been made, we may relate an incident which occurred in the Colonial Hospital. The copy of the work sent there wholly engrossed the attention of the natives, the best reader was selected to read aloud while the other Maories formed a circle of most attentive listeners, they could hardly be persuaded to allow the lights to be put out at night, and the next morning as soon as there was sufficient light the reading of the interesting story was resumed.”

There are no known records of the actual number of sales and how many copies reached the target market: Māori. What we do know is that Kemp gave some copies of Ropitini Kuruho to his European and Māori friends, and Rogers says that “many of Kemp’s printed texts were distributed through the Office of the Native Secretary and the network of government-supported schools.”

Grey sent some copies to Earl Grey in London in June 1852, describing the book and the work already underway on Pilgrim’s Progress as instructive and adding impetus to “the rapid advances the natives continue to make in the arts of civilised life,” reflecting the prevailing view of European superiority. For him, to ‘civilise’ was to Europeanise, to assimilate. He expected that the publication would make a profit. His report to the British Parliament that the book was avidly received by Māori.

Despite this and The Independent’s confidence that the book would be a best seller requiring a second edition, the only advertisements of the book for sale identified in PapersPast were run by The Spectator, and they continued until at least the 9th November 1853.

As with Defoe’s original audience, books of “realistic fiction” were a new cultural concept for many Māori to get their heads around. The subtle publishing convention of naming Defoe as the author that provides the clue that the work is fiction was also likely a new one to many Māori readers - this is a culturally transmitted piece of knowledge. So for example, Assoc Prof Mark Houlahan recounts a story from the Crown Law Office of a rangatira who was unwilling to sell his lands, saying that they were intended for Crusoe when he came.

In 1900, Thomas Hocken stated that when “the inevitable Killjoy made it known that [Crusoe (1852) and Pilgrims Progress (1854)] were allegories … all interest ceased.” The series was not continued or reprinted.

Rogers argues that Hocken’s reason is too simplistic. The rapid growth of the Pākehā settler population was accompanied by a government push for Māori to be educated in English. Growing Māori disenchantment with Pākehā behaviour that did not live up to the Christian precepts taught by the missionaries undermined the church’s sway, and the European perception of peaceful race relations celebrated in those initial reviews of Crusoe were swept away with the outbreak of the Taranaki War. Māori started to print their own material.

At least some of the Ropitini Kuruho copies appear to have been accompanied by a Māori language notice by Kawana Kerei (ie Governor Grey) again printed by The Independent. Dated July 1852, it is headed ‘He Pukapuka Pa Nui’ - the book notice, and addressed to both men and women. This type of publication is the kind of loose sheet that tend to get lost or recycled, described by historians as ephemera.

For all the alleged loss of interest by Māori, in an 1868 letter from Sir Donald McLean (1820-1877) to William Colenso (1811-1899), he complains, “I’ve had some trouble in getting a “Ropitini Kuruho” and at last I had to borrow the library copy, when I discovered that Mr Lyon had one which he would lend if necessary. I went to all kinds of places in search of one. I send you ‘Pilgrim’s Progress.’” The latter presumably referring to the Kemp translation, He moemoea, published in 1854.

Lyon is most likely to be William Lyon (1805-79). Born into a family of booksellers in England, he continued the occupation when he moved to New Zealand. According to Sholefield, Lyon had been involved in the establishment of two newspapers in Wellington - including The Independent. He also collaborated with Robert Stokes from The Spectator on some projects – the newspaper that retailed the book. He was also a member of the New Zealand Society.

McLean could have met Lyon in Wellington or in Hawkes Bay where they both had property. Lyon was described by in the 1940 Dictionary of New Zealand Biography as a great reader who possessed one of the best libraries in New Zealand at the time. He was also involved in setting up New Zealand’s first public library in a native house built originally for Dicky Barrett next to Barrett’s Wellington hotel – another incidental link to Taranaki’s colonial history.

The Puke Ariki copy has forgone the cheaper paperback covers, hard bound at some point with a leather spine embossed with the title in Māori picked out in gold lettering and leather protected corners over marbled paper in a style typical of the 19th Century for those who could afford it. Fortunately for us, that previous owner had the Pukapuka pānui tipped (glued along the edge) into the binding (see page 1 and page 2).

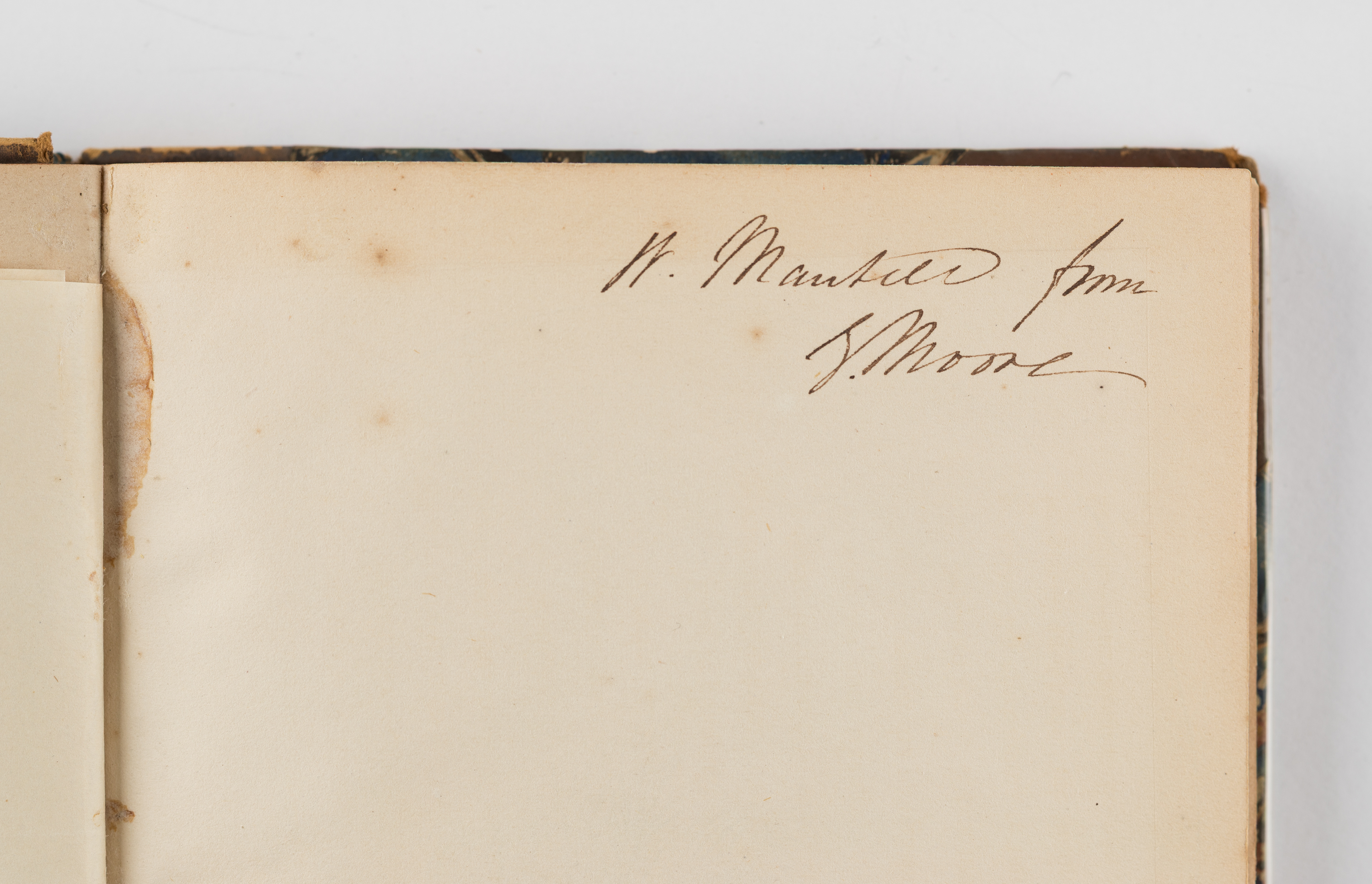

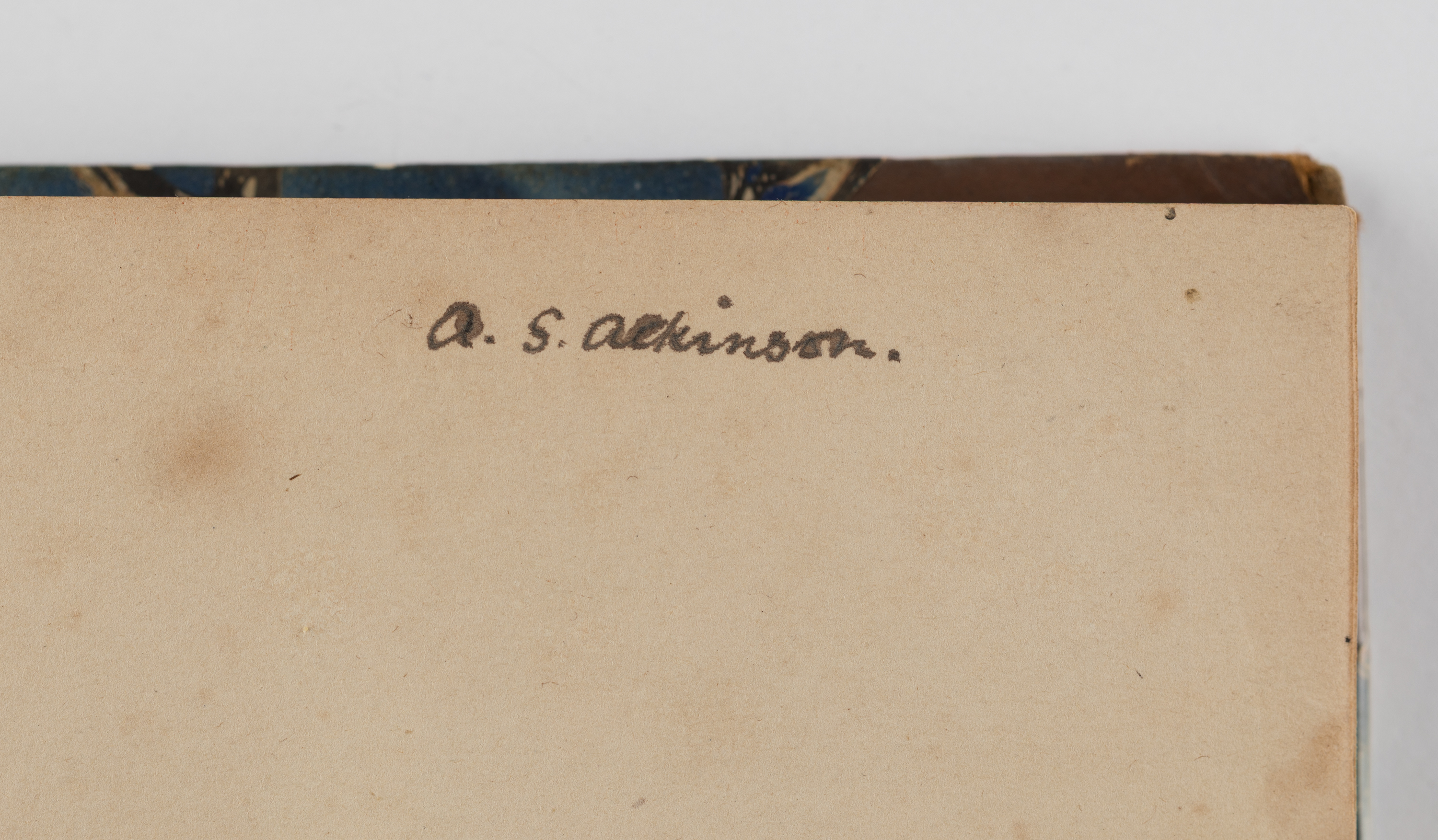

There are three handwritten inscriptions in the front of the book hinting at some of the hands this book passed through on its way to the library.

On the Māori title page is a difficult to read inscription in Māori, kindly transcribed by Prof Lachy Paterson: “Kia Matara [or Matura] / Na tona hoa aroha / E. Moa [or Mou].” Paterson was not sure whether the recipient had a Māori surname or whether it was an attempt at a transliteration of a European surname such as Muir.

Another inscription is to “W Mantell from G Moore”. Based on the handwriting, this was George Henry “Scabby” Moore (1812-1905), who became one of the wealthiest men in New Zealand. The recipient is perhaps Walter Baldock Durrant Mantell (1820-1895); there is evidence of at least one letter between them. Mantell was the first secretary of the New Zealand Society in Wellington in 1851 and a Mr Moore was there, but without a first name we can’t say for certain it was George. (A Mr Lyon and a Mr Stokes were also present. As mentioned previously, the Pākehā population was tiny!)

Tantalizingly, in the Mantell Collection of books in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington what sounds like the same panui was bound with He pukapuka ako tenei i nga ritenga pai e-maha o roto o te taonga nei o te moni. Poneke: Te perehi, o Te Kawanatanga o Te Kuini, 1851. A spelling book for the use of Māori children, Wellington, N.Z.: printed by R. Stokes, 1852. Was binding related ephemera into books his common practice?

If Walter Mantell is correctly identified as the owner, one wonders if the gift was made before Mantell’s relationship with Kemp soured. Kemp had been made redundant from government work in 1865, later, claiming that this was due to the influence of Walter Mantell (the Secretary for Native Affairs at the time). Kemp had described Mantell a “cowardly and Jesuitical liar” in relation to a sex scandal involving Mantell and Māori women. Perhaps Ropitini Kuruho was handed on due to these negative associations?

The other inscription on the front flyleaf of our copy in a small, tidy hand is “A S Atkinson” which matches the even tinier pencilled annotations throughout the text. Sure enough, the signature matches that of Arthur Samuel Atkinson (1833-1902), a well-known member of a Taranaki family associated with Hurworth House. These local links suggest that this was probably the last of the inscribed owners, and a part of the reason it eventually ended up at the New Plymouth Public Library.

Frances Porter, Atkinson’s biographer, notes that he had been a keen student of the Māori language from at least 1860, and that he frequently annotated his books. His annotations of the Ropitini Kuruho text start out as brief comments that sometimes suggested that his vocabulary was being stretched, and the odd correction (see photograph). About 20 pages in, he swaps to simply noting a sequence of numbers. Finally, inside the back cover is a small index.

The Taranaki Research Centre’s companion copy of Bunyan’s He moemoea… (1854) has a completely different binding, suggesting we acquired the two titles separately, and sadly the first few pages are missing so we have no record of previous owner(s), if any.

There is still much about this book that we would love to uncover, in particular, who the Māori inscription refers to.

It would also be great to join the dots if we could find Atkinson’s separate numbered annotations that acted as a key to his numbered annotations – perhaps they still lurk amongst his papers in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, equally perplexing researchers there!

The accompanying ‘He Pukapuka Pa Nui’ does not appear to have been translated into English: it may provide further insights into the history of this publication, as would comparing it with the copy in The Mantell Collection at the Alexander Turnbull Library along with the binding style. At the time of writing, this item was unavailable.

More broadly, New Zealand print culture historians Houlahan and Rogers think that a survey of the remaining 19th Century books in Te Reo, especially translations from English, would provide a real advance in our understanding of the period. Even better if the survey documented who owned the specific copies and any signs of use or response to the text. Of the copies of Ropitini Kuruho that Houlahan was able to look at - all in library collections - none appeared to have belonged to Māori. Instead, in his opinion all appeared to have all been purchased by Europeans as items of New Zealandia. Writing in library copies is frowned on and historically it was often the most pristine copy that was kept, so it would be useful to view any copies still held by families as part of the survey.

Note: This piece was written in celebration of Te Wiki o te Reo Māori - Māori Language Week, September 2025.

Bunyan, John. He moemoea: otira, ko nga korero o te huarahi, e rere atu nei te tangata i tenei ao, a, tapoko noa ano ki tera ao atu. Poneke [i.e. Wellington, N.Z.]: Te Toki, 1854.

Bunyan, John. He moemoea: otira, ko nga korero o te huarahi, e rere atu nei te tangata i tenei ao, a, tapoko noa ano ki tera ao atu. Auckland Council Libraries Special Collections, GNZM 262, Copy 1 marked-up by T C Kemp for the proposed updated edition.

Defoe, Daniel, He korero tipuna pakeha no mua, ko Ropitini Kuruho, tona ingoa Aperira [Wellington]: [publisher not identified], 1852

Defoe, Daniel, He korero tipuna Pakeha no mua, ko Ropitini Kuruho, tona ingoa. Auckland Council Libraries Special Collections, GNZM 243, Copy 1 marked-up by T C Kemp for proposed updated edition.

Higgins, Rawinia, & Basil Keane. Te Reo Māori – the Māori language, Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-reo-Māori -the-Māori -language (accessed 9 Sept 2025.)

Houlahan, Mark. The Canon on the Beach: H T Kemp Translating Robinson Crusoe and The Pilgrim’s Progress, in Voyages and Beaches: Europe and the Pacific, 1769-1840. Honolulu: Uni of Hawai’i Press, 1998, pp. 304-316.

McLean, Donald, to William Colenso [letter], 16 Oct 1868. ATL MS-Papers-0032-0222 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/manuscripts/MCLEAN-1020251.2.1

O’Hare, John. Kemp House slate sparks ‘missing person’ enquiry. Heritage New Zealand. 30 May 2023. https://www.heritage.org.nz/news/stories/kemp-house-slate-sparks-missing-person-enquiry

Parr, C J. ‘Māori literacy, 1843-1867,’ Journal of the Polynesian Society 72 (1963):211-34

Rogers, Shef (1998). ‘Crusoe Among the Māori: Translation and Colonial Acculturation in Victorian New Zealand’. Book History. 1(1): 182- 195. doi: 10.1353/bh.1998.0007 . ISSN 1529-1499.

Scholefield, G H (ed.) William Lyon, Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Department of Internal Affairs, Wellington, 1940, Volume 1: 511.

Please do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.