Nature has:

No corners

No errors

No ends

No fractures

No self-starters

No self-control

Nothing independent

The circle is spiritual. The square is material.

Love is curved. Hate is a straight line.

A halo contains no right angles. The Cross has 12. The swastika has 20.

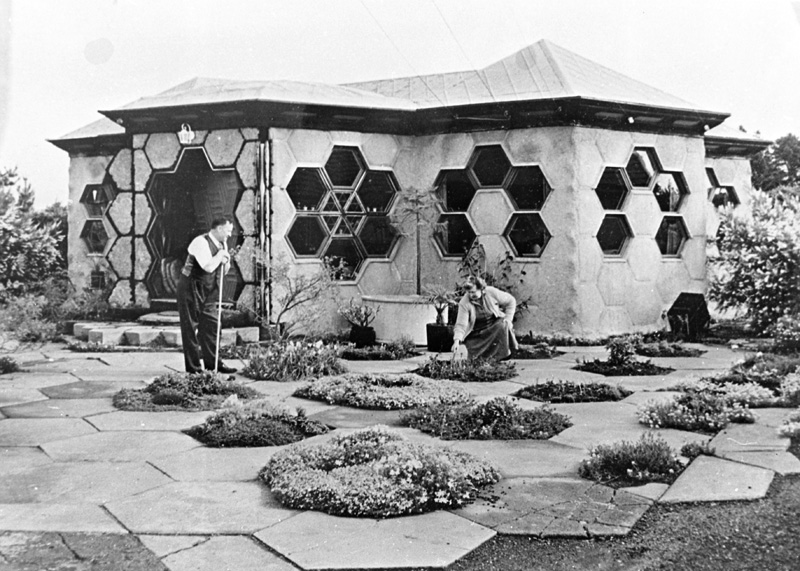

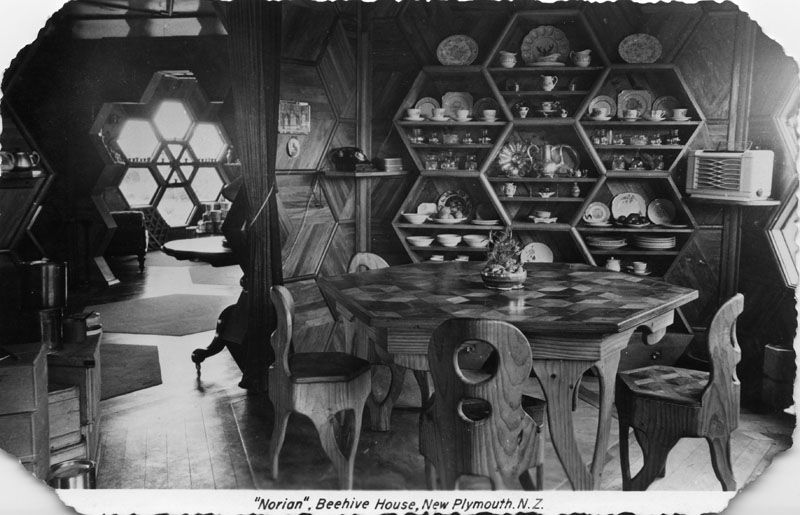

In Edgar Roy Brewster's house, even the Mona Lisa is hung in a hexagonal frame. Photos, saved for posterity, had all their corners cut off. In the master bedroom, the bed bore a hexagonal quilt and the cover a scalloped hem. Mirrors on the wall were round. Everything about the house was hexagonal, diamond or triangle shaped, nothing at all was square. The roof was a hexagonal pyramid and outside the front door lay hexagon paving with the odd one omitted and small gardens planted in the space.

A visitor once wrote: “Anybody who has visited Norian will have embedded on his memory the picture of the large Taranaki farmer type with a small moustache, striding up and down talking animatedly about aeroplanes and philosophies, waving photographs and diagrams.”

Brewster believed in God - and Eskimos who built their houses the right shape. He spent much time reading his bible, particularly the Book of Revelations, always coming up with fresh interpretations. He believed in bees - everything the bee did was perfect, from the way it flew and gathered food, to the way it conducted its social habits. But it was the way a bee constructed its house that impressed and consumed him most.

“Why does a man try to do everything square?” Brewster wondered. “Nothing in nature is square. Man is a square peg in a round hole. Honeycomb and eggs are the most perfect constructions for their purpose.” He believed man was making a huge mistake using a shape that was 500 years out of date.

Brewster said: “When Columbus discovered America in 1492, it brought about a great change in thought. Until then it was accepted the world was flat. That was a religious teaching. After that it was realised the world was round. Instead of changing to round principles, man has gone merrily on his way, still acting as though it was a flat square. He continued planning his cities on the square and generally acting on the wrong principles altogether.”

A square could not be strong without triangular bracing. So he set about eliminating all right angles from his life.

Brewster's interest in bees began when he collected a small swarm from a gatepost when he was 14. What began as a purely money-making venture would soon develop into a life-long obsession.

Even as a school boy, Brewster had considered himself destined for some kind of greatness, and he thought it might have been at rugby. Eventually, he played for Taranaki. Rumour has it that when he left for a match in Gisborne, instead of travelling by bus with the other players, he drove his truck and delivered honey on the way. As someone later remarked, it might have been good for business but not for comradeship. In 1960, according to his advertising, Brewster sold 2 pound tins for 5 shillings each. His letterheads read: 'Orders promptly attended to in winter months. In summer, bee work often has to come first.'

He decided beestings were “a kind of escapism” that sharpened his mind and gave him wildly interesting thoughts. “'Beekeepers usually suffer many stings in the course of a day's work and it is likely that my share has been at least one quarter of million,” he wrote in his hexagon-shaped Norian souvenir booklet. “The result of thousands of bee stings and the pain thereby suffered causes a thoroughly shocked condition and a tremendous intensity in which one vibrates at a higher rate than normal. The result of such stimulation is that one...acts like a bee, thinks like a bee and becomes hexagon-minded...”

Brewster was always a man of strong ideas. He asked questions and answered them himself. Watching birds in flight made him wonder if aircraft should be modelled on quail or seagulls. Seagulls needed considerable airspeed before they could fly, whereas quails were instantly in flight with a whirr of wings.

Aircraft designers made their planes to first glide without power then put power into them. Could they have made a serious mistake? “As a result of a fantastically realistic series of vivid dreams about levitation and flying,” he was to say, “I developed an intense interest in the subject. I was then about 23 and had not long begun life as a commercial bee keeper. I will never be done with experimenting but will always allow myself to be guided by a higher power in what I do.”

The vision of flying started soon after he married and was reinforced by his first flight in 1929 in a wealthy uncle's new plane. Soon Brewster's inventive zeal turned his wife Beth's umbrella into a powered parachute. The results were not encouraging and for a while his experiments were put aside.

During the next few years he tried his hand at different things. He opened a shop in Devon Street selling honey and ponga pots. His carved pots were interesting and sold well until the local market was swamped. Brewster planted palms in the remainder and established a thriving plant hire business which he sold to an employee. He had a very successful honey season, and subsequently sold his bees to another beekeeper which provided cash for further aviation experimentations. Later, he would buy his bees back, and resume beekeeping.

At 17, Bob Wallath's head had been turned by Dick Turpin and Satan. The son of a respectable farmer, he would don a mask and cloak at the edge of town and take a few purses, before changing into his best clothes and sauntering into New Plymouth by a different route. Eventually Bob was given the task of escorting girls home to save them from his own wicked alter ego.

The Highway Man ran aground when he robbed the Criterion Hotel at gun point and was captured. But jail had a good effect and after one escape Wallath repented and went straight. As Brewster's neighbour and mentor, he often helped him out when he was in financial trouble, until even he said, “No more experimenting!”

Soon, there were eight mouths to feed. Two of the Brewster boys had been born totally deaf, but still Brewster followed his crude principles into 100 pages of aviation theory. He built model planes, some of which flew exceptionally well. Patents were gathered from England, Canada, USA, Australia and New Zealand. It was time to build a full sized plane.

Enter the Flying Flea. When people saw it, they laughed. A small aircraft built by two Stratford men, it was controlled by altering the pitch of the wings. The same model had killed a number of people in France and Brewster got it free. Though he planned to use only the engine, he found himself tempted to fly it before dismantling began.

Out at the Bell Block Air Pageant he took to the air without a pilot's licence after being in a plane twice. Flying was limited to 15-20ft maximum height without a pilot's licence. Other licensed pilots had tried to fly the machine without success, so he was curious to see if it would lift off the ground.

Roy was 14-15 stone which was overweight for the aircraft. The plane taxied across the field, hurtled back down, flapping its wings until it bucked like a horse. Backwards and forwards it went with Brewster at the controls and a man on a motorcycle keeping pace. One great heave and the plane almost stood on its tail. Then it flew.

The next seven years were lean ones for the Brewster family. Beth died, the honey season failed and they were constantly in debt. The world lurched into World War Two. The Bee Man's two deaf sons came home from the Sumner School. He couldn't keep his housekeepers and had little time for his bees.

In 1947, Brewster married Nettie Heal and in an odd fit of romanticism hired a New Plymouth Aero Club plane to drop rose petals over the bride as she left the church. A cloud of petals drifted down all over town instead. Nettie called him her “worker, husband, lover and prophet”.

Brewster turned to God and discovered hexagonal thinking. “The right angle and the square no longer go unchallenged!” he preached. “There are better ways!” As he worked on his first six-sided structure - a henhouse with a domed roof - a reporter turned up and an article appeared in the paper the next day. Visitors began arriving unannounced. Brewster seized on a new opportunity - that of building a six-sided house, aided by his three sons.

Behind Brewster's plans for a beehive house lay years of frustration and despair, as well as abiding hope. As his writings show, he thought this idea might well win money as well as fame.

When the remarkable Norian was finished, Brewster must have felt his future was finally assured. Overseas magazines Pix and Popular Mechanics knocked on a door that was never locked and at least five films were made. Guests were welcome to show themselves around if no one was home. An honesty box sat on a table next to goods for sale - sheets of music, honey and little hexagonal-shaped information booklets - while a Chinese coin cabinet offered change if it was needed.

A baby grand piano stood in one room, where Nettie composed music while Roy wrote the words. It was the odd man out in a home where the inhabitants embraced and exhorted 'living in the round'. The grandfather clock was in a similar category.

Over the next 20 years more than 250,000 curious visitors flocked to Norian as bundles of visitors books can attest and yet no charge was ever made. Rather than charge admission, Brewster had thought to pitch his grand ideas of massed produced prefabricated hexagonal housing to a captive audience but found no takers. When he heard of plans to extend Parliament buildings by the construction of a large 'Beehive', he pitched his ideas there.

It seems no one was interested in prefabricated hexagonal buildings. On the 6th day of the 6th month, 1966, Roy Edgar Brewster sold the land under his house to the nearby church for £6,666. What was quite likely meant as a publicity stunt, the church considered it simply a business deal at a bargain-basement price. On the hill where the Bee Man had once pictured a whole village of round houses, a sharp cornered old folk's home loomed large.

Full of disappointment, Brewster dismantled Norian wall by wall and trucked it to Egmont Village where it was never rebuilt. His reign as the innovative Bee Man was over, though he continued making hexagonal structures in a disused dairy factory he owned nearby.

In 1973, on the night of Nettie's death, Brewster had a vision of a new hexagonal Jerusalem rising from the scrubby slopes of Taranaki. Despite all efforts to convince the Inglewood County Council of its merits, his plan was turned down. He died in 1978, a disappointed man.

As a visitor once noted, “Brewster is a very convincing talker, but when he starts talking about God and the Book of Revelations, they shake their heads and leave. He's a crank. They are safe again. They dismiss him and his theories.”

But Brewster cannot easily be dismissed as a crank. Everything he did followed experience. His philosophies were often coherent, logical and convincing. Yet a trawl through Puke Ariki's extensive archives reveals his writing degenerating over time, from steady, well-written passages to solid blocks of underscored and capital lettered prose. Both his health and his eyesight had deteriorated due to bad diet and lighting.

Perhaps, in the end, the Bee Man had simply got caught up in his own sticky web of alternative bee thinking, forgetting that he was really just a man.

Puke Ariki Heritage Collection: Roy Brewster

LinkPlease do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.