For six sunny days in 1958, New Plymouth experienced the glamour and excitement brought by a group of visiting American sailors. The icebreaker USS Staten Island docked in the city before heading to Antarctica as part of Operation Deep Freeze IV. Many of the crew were billeted to local homes on the goodwill visit and enjoyed a range of activities during their shore leave.

Operation Deep Freeze was a series of scientific research missions to Antarctica establishing an American presence on the ice which has lasted to this day. Those on board the 6500-tonne Staten Island helped build bases and undertook various experiments, including measuring water and air temperatures, taking biological samples and analysing cosmic rays. They also took part in a large health study on the common cold, involving regular nose and throat swabs, dubbed Operation Snuffles.

The ship left its home port of Seattle on 28 October 1958 and arrived in New Plymouth at 1.30pm on Monday 17 November 1958. It was the first American vessel ever to visit the Taranaki port so the 247 crew and their captain, Commander Price Lewis, were greeted with a pōwhiri by a Māori cultural group before a cheering crowd. The next day 150 sailors paraded down Devon Street in the central city for 10,000 onlookers. Schools were allowed to close early so children could enjoy the spectacle and a group of boys rode their bicycles alongside the men as they marched in formation. The New Plymouth City brass band accompanied them as they saluted Mayor Alfred Honnor on his dais near the intersection with Egmont Street. The icebreaker’s two helicopters hovered over the parade route beforehand, and office workers were seen leaning out windows and on top of buildings to get a better look at “the Yanks”. Commander Lewis addressed the crowd: “I will be very brief and sincere. We are overwhelmed by the hospitality that you have shown us.” This hospitality extended to accommodation, with billets in private homes arranged for at least 30 of the crew keen to experience Kiwi life up close.

New Plymouth’s public relations officer, Eric Handbury, organised various outdoor activities for the men during their stay but cutting a rug was also on the agenda. To celebrate the ship’s visit, a “Festival of Dancing” was held on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday night at the Star Gymnasium, the city’s largest hall. Season tickets costing ten shillings (about $24 today) could be bought for those with the stamina to bop all three evenings away and special transport was put on to bring people in for this “dancing jamboree” from as far afield as Stratford. The hall was specially decorated with “soft, coloured lights” and couples could enjoy a “continuous special supper” to the tunes of local bands like the Rhythmics, the Lambert Twins, Colin King and the Harmonisers, and the Kathleen Haire Tango Team. A dedicated rock’n’roll corner was set up, but advertisements promised to leave “oceans of room for ballroom dancers”. The first night of the festival was attended by 190 sailors so the young women of Taranaki could take their pick. Several of the Americans even helped with the dishes afterwards, such a novelty at the time that it was photographed by the press.

"Welcome USS Staten Island"

The town did everything it could to make the men feel welcome, including turning on the illuminated fountain in Pukekura Park every night of their visit. A cold snap on the Monday caused mild panic, with a sprinkling of snow on the mountain, but no rain, to the great relief of all concerned. The weather was “very well behaved” after that according to the Taranaki Herald, which declared that the sunny skies must be due to the presence of the ship, dubbing it “Staten Island weather” – never mind the fact that November in the real Staten Island would have been significantly chillier.

Retailers were keen to cater to the tourists, festooning their stores with American flags and signs featuring the Statue of Liberty saying “Welcome USS Staten Island”. According to bank tellers, one dollar was worth seven shillings at the time (nearly $17 today) so the men’s buying power was considerable. Local milk bars were said to be “intrigued by the Americans’ requests for ‘fried egg hamburgers’ and ‘all coffee, no milk’”. Residents were allowed onto the Staten Island between 1-4pm to explore the ship. An average of 1000 people boarded every day it was docked, more than a fifth of the city’s population. A local priest, Father James Austin, even performed a mass on the flight deck for Catholic crew members.

People were clearly fascinated by their exotic guests, the papers publishing dozens of articles about the Staten Island and its men, who came from all over the United States. Of course the question we always ask any visitor is how they like New Zealand, and a reporter from the Taranaki Herald conducted interviews with a range of crew members to find out just that. They were unanimous in their praise of Taranaki’s hospitality but noted the lack of neon signs and traffic lights. New Zealand beer was apparently darker and heavier than American, and the taste of a cuppa was another difference, sailors describing how they served the beverage back home in “a cup of boiled water with a small bag of tea which is dipped in the water” – it would be another 11 years before Kiwis were introduced to the wonders of teabags. But it was the local girls they were asked about most often, and opinions were somewhat mixed. Radar Operator Bob Moyer from Pennsylvania thought New Plymouth girls were “sturdier” than their American counterparts and Engineman Jim Hall from California agreed, describing them tactfully as “less fragile”. Others were more generous with their praise: Electronics Technician Jack Clark from Illinois found Taranaki ladies “very attractive” and Gunner’s Mate Raymond Wasson of Mississippi claimed that they “really go all out to make sure you enjoy yourself”.

"The locals rolled out the red carpet"

Lieutenant Jim Freund from New York, now 87, served on the USS Staten Island for three years. He shared his memories of those six days in New Plymouth with me earlier this year, and they were all happy ones. Jim recalled that “the locals rolled out the red carpet” and “plied [us] with food and drink”, remembering “how impressed we all were with your fair city and its inhabitants”. He said his “strongest memory is a day spent at Mt Egmont (your own Mt Fuji)” but that he also found time to fall “in love with a charming lass – a three-day relationship doomed in the end by my never returning to New Plymouth.” Other sailors also made fast work. Mere hours after their ship berthed, one group had “cleared their driving licences with the Transport Department” and hired cars and scooters for the week, keen “to see as much as possible of Taranaki” despite the fact they would have to travel on “the wrong side of the road”.

Wednesday 19 November saw ten sailors taken fishing in the Waiwhakaiho River and five playing a round at the New Plymouth Golf Club. Fifteen men were woken at 1.30am to go hunting in the bush around Whangamomona, where they caught nine wild pigs, proudly cutting the tusks off a massive boar in order to display them back on the ship. On Thursday another group of ten sailors climbed to the summit of Mount Taranaki, treated to a picnic afterwards with the Women’s Division of Federated Farmers. Guided by members of the local Alpine Club and three park rangers, the men were photographed enjoying cigars atop the peak. A cartoon was printed in the next day’s Taranaki Herald imagining a sailor scrambling up the side of the mountain, beer bottles flying out of his satchel, crying “Boy, oh boy! Stand by with those ‘cokes’ Al, we’re just about there”. Meanwhile, the ship’s helicopters were being flown to Highlands Intermediate where they were cheered by hundreds of pupils from local schools. After enjoying morning tea and signing autograph books, the pilots put on a show for the kids, circling the playground and picking up a man from the ground whilst airborne. The two helicopters entertained the city on other days too, circling the mountain and landing on Ngāmotu Beach.

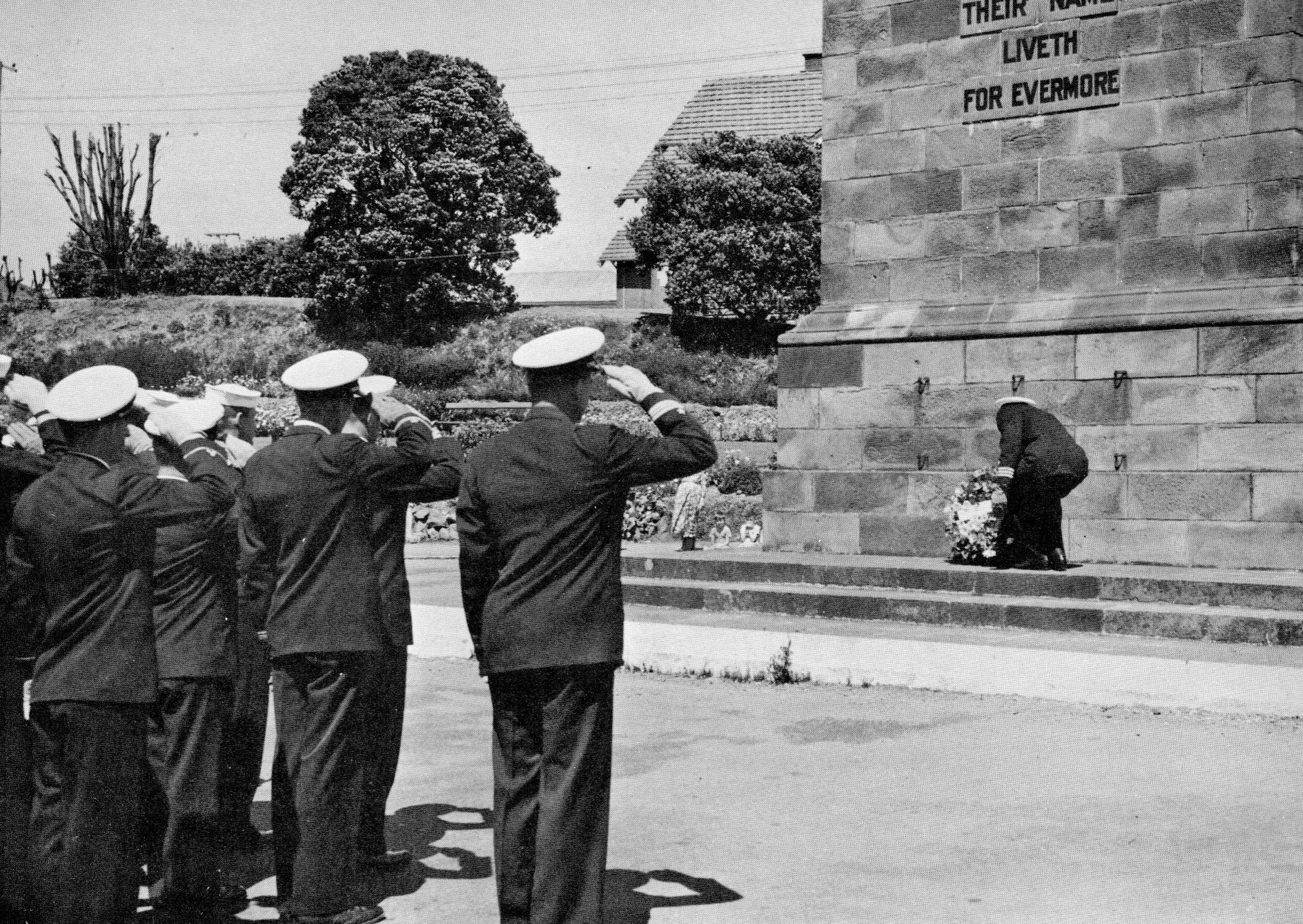

Friday night saw the Americans put on an exhibition game of softball under floodlights at Pukekura Park. The crew formed two teams, officers against enlisted men, and played “with full time commentary for the pleasure and amusement of New Plymouth citizens”. Organised by the Taranaki Softball Association, an admission fee of one shilling (six pence for children) was charged, with all proceeds going to the charity of Commander Lewis’ choice. Over 3000 people attended, raising £122 for the Intellectually Handicapped Children’s Parents’ Association. The spectators loved the “razzing” each team gave the other (not to mention the umpires) with the enlisted men, clear crowd favourites, winning 22-9. The day before the ship left port a group of 21 Staten Island crew laid a wreath at the foot of New Plymouth’s Cenotaph at the intersection of St Aubyn and Queen Streets. All had served in the Second World War and were entertained accordingly afterwards at the local RSA clubrooms.

"We'll be back someday"

The Staten Island left New Plymouth at 7.30am on Sunday 23 November, waved off by a crowd of thousands. Families who had billeted a sailor brought farewell gifts, and the ship underwent a routine check for stowaways, although Ensign D. Pizinger of Kansas remarked that “anyone who’d stowaway to where we’re going would have to be crazy”. The papers noted “a few sad-eyed girls” in the throng, some of whom were thrown notes by sailors as the ship pulled away. Others threw their hats, with local teen Neville Roebuck cheered heartily by the crew for jumping into the water to retrieve one, presumably intended for somebody’s sweetheart. Written inside was “We’ll be back someday” and “Love, Danny”.

Mayor Honnor was allowed to steer the ship past the breakwater, returning to port on a pilot boat afterwards. Back on his desk in the council chambers, he found a brass plaque left by Captain Lewis inscribed to the people of New Plymouth “in appreciation of their hospitality”. The captain’s official farewell message promised to take “glowing reports of New Zealand and especially New Plymouth” to the USA. The Staten Island left Lyttelton for McMurdo Sound two days later. Her crew spent three months in Antarctica under a sun that never set, playing ice football and catching penguins in their free time. The ship finally returned home via Australia and Niue in April 1959.

The visit of the Staten Island to New Plymouth in November 1958 was seen as a symbol of vital trans-Pacific friendship at a time when the United States, in the aftermath of World War Two and with the Cold War well underway, had never been more powerful. Editorials reminded readers that in an emergency situation the crew of the Staten Island “would be diverted to Pacific defence duty”, alongside Kiwi and Australian naval units, to act as our “sentinels”. The Taranaki Daily News pointed out that the USA had replaced the United Kingdom “as the big brother on which New Zealand must lean in times of trouble” and that, with “the great upward march of the peoples of Asia” compelling “both admiration and fear”, America was “almost the only guarantee of New Zealand security and independence”. The Daily News was comforted to find that “the average American is not as Hollywood or Moscow paints him” but still described the ship’s visit as bringing “the breath of another world” to “our own little insular paradise”.

This article was originally published in New Zealand Memories magazine #154 (February/March 2022).

Sources

Taranaki Daily News and Taranaki Herald, 1-24 November 1958.

New Plymouth Photo News, 27 November 1958.

Please do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.