Tim Chadwick's father grew up on South Road, Hāwera, next to the Morrieson house and often told tales of the author arriving home at dawn, in his great lump of a car, so boozed up he would fall asleep at the wheel. It only added to the curious shine of the man's reputation, and a glimpse of Ronald Hugh Morrieson's face at the attic window, would stay with Chadwick for all time.

But it wasn't until the movie The Scarecrow came out and Chadwick began collecting the original posters, that he realised what a brave literary talent Morrieson was. “Some of the things in his books, like rape, incest and murder - I mean, they weren't talked about, they were brushed under the carpet in those days.”

In 1992, when KFC announced they would bulldoze Morrieson's house and build a restaurant on the spot, Chadwick was galvanised into action. “Katherine Mansfield's house had been saved, Rita Angus's cottage had been saved, Frank Sargeson's shed had been saved and I thought, this is a great opportunity for Hāwera.”

To Chadwick, it was a multi-levelled thing. As well as being a resounding literary voice, good enough to be studied in the Scottish educational system, Morrieson was one of the first writers to have an empathy with Māori characters. “There was a real kiwi thing in there. I support a lot of initiatives where Māori sites are preserved and this was an important piece of Pākehā culture. It almost felt that because it was Pākehā culture it was being overlooked. I was annoyed, and then I found that there were other, older, people who knew Morrieson, and who knew him as a good person, and they wanted it saved as well.”

He spear-headed the Scarecrow Committee and launched into a battle to see the author's house saved. “Clive Cullen, the Hāwera architect, got right in behind it, and Mary Bourke, the Mayor. She was a newbie at the time and she voted to save the house in some form, whereas most of the council wanted it to go. We had Geoff Walker, publishing director of Penguin books, who wrote to the mayor and said it should be saved. We wrote to the Minister of Cultural Affairs, the Minister of the Environment, the Minister of Conservation, Prime Minister Jim Bolger - we tried everything. We even wrote to KFC.”

Despite the raft of “lip service letters” that came back, the committee held fast to their belief that the house should be listed as historic and worth preserving. “We were trying to get some official body to step in and make it an historical building so even if it was moved, it could be saved. We thought it could be an information centre, and someone wanted it for a hospice but we didn't think that was right.”

The fight for Morrieson's house divided Hāwera citizens - and not neatly down the middle. While some were apathetic, some were openly hostile. Many thought bringing KFC to town was a fine thing and a good way of ridding the place of Morrieson's unwanted ghost. After all, the man had had the temerity to place the characters of his books on a thinly disguised Hāwera stage.

When Chadwick began to collect signatures for a petition to save the house he was subjected to malicious phone calls and abuse. “Some of them were quite nasty. I had one woman who rang up and said, 'Why do you want to save the house, he used to leer at our daughters.' What does that mean?”

While his petition drew 60 signatures, an opposing one drew a staggering 1300. “A lot of people didn't care because they didn't think he was special,' Chadwick says. 'Even some of his old band mates were quite happy to see KFC go up.”

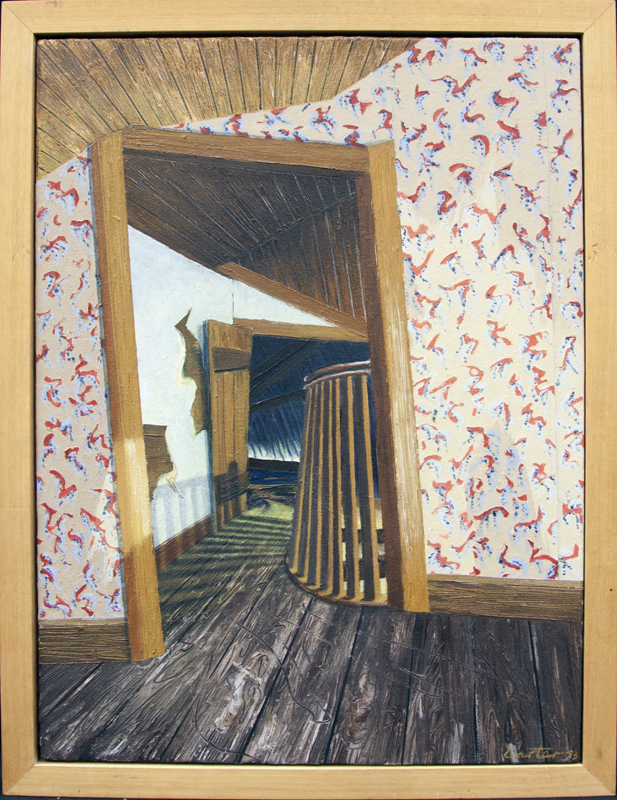

Sadly, the Scarecrow Committee found itself outgunned and KFC built the following year. Chadwick still feels Hāwera lost out on preserving an edifice that could have drawn many tourists in. “There was a furniture factory in the house in the end, but aside from a wall being taken out, it was still the same as it was in Morrieson's day. You went up to the attic and the old wallpaper was still on the walls.” It would be amazing if Morrieson's loft could still be used, he says. A contractor brought in to bulldoze the house couldn't bear to destroy it completely, so the attic still sits on a farm somewhere, covered by a tarpaulin.

Chadwick tries to remain philosophical about the house. “In some ways, it serves us right. We just presumed it would always be there.”

Millen, J. (1996). Ronald Hugh Morrieson: A Biography. Auckland: David Ling.

Morrieson, R. H. (1964). Came a Hot Friday. Sydney: Angus & Robertson Ltd.

Morrieson, R. H. (1976). Pallet on the Floor. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Morrieson, R. H. (1981). Predicament. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Morrieson, R. H. (1963). The Scarecrow. Sydney: Angus & Robertson Ltd.

Puke Ariki Heritage Collection: Ronald Hugh Morrison

LinkPlease do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.