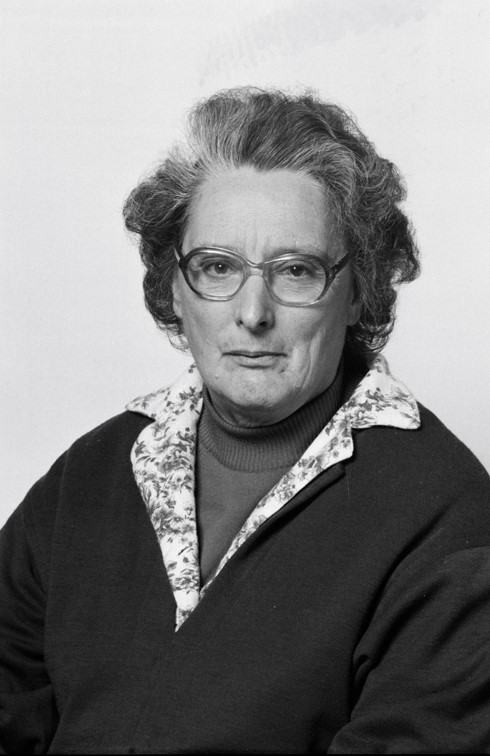

In 1983 a New Plymouth school teacher in her 60s captured national attention - not for her career (though that was notable) nor her wealth or family connections – but for her formidable intellect.

When Ida Gaskin won the hugely popular televised final of Mastermind in 1983 with her specialised subject of Shakespeare – she became the first woman to do so.

Her victory was more than a personal triumph—it was a symbol of how she had lived her life and how she intended to spend the years ahead: fully engaged, intellectually curious, and embracing life in all its richness.

Ida’s win challenged stereotypes about age, gender, and retirement, and it marked the beginning of a new chapter in her life—one she approached with the same fierce energy that had carried her through decades of teaching, life as an immigrant, motherhood and political and community work.

Her attitude to retirement remains refreshing and challenging today as it did in 1989 when she delivered a speech titled “The Myth of Retirement” during the centennial celebrations of Stratford’s St Andrew’s Church.

That speech, preserved in Puke Ariki’s Oral History Collection, was recorded when Ida had retired from teaching. But rather than viewing retirement as a time to slow down, Ida saw it as a period of liberation.

“The greatest moment of my life was when I suddenly looked round and realised that for the first time in my life, I was my own person. I wasn't a child, a daughter under discipline from my parents. I wasn't a pupil under discipline from my teachers. I wasn't a student under discipline from the examination system, which is another myth that I'd like to deal with. I wasn't a mother. I wasn't even a wife, fortunately, by that time. I had no responsibilities to anybody I could do. For the first time in all my life, 60 years, I was free to do exactly what I liked, when I liked, how I liked, whenever I liked. It's the most wonderful feeling of freedom.”

Ida was a woman of conviction and razor-sharp intellect, unafraid to challenge ageism or sexism, and determined to make the most of her later years.

“But I will not sit at home with my knitting, twiddling my thumbs, pretending that I am a moron when I think I my brain is still working as well as ever. I certainly talk more than ever. I read the same things as I used to read, and I have certainly have a far happier, far fuller and far more exciting life than I ever had when I was working.”

Her retirement plans were ambitious and inspiring. She intended to learn Greek to read Sophocles in the original, and Russian to read Tolstoy. She wanted to study New Zealand poetry and return to London to see Shakespeare performed live. She also considered more leisurely pursuits like growing roses and learning embroidery.

Far from fearing a loss of identity in retirement, Ida believed strongly in the value of community involvement. She argued if you want to be useful you must make yourself so and one easy way to do that was to work organisations that rely on volunteer support.

“They say you should find an interest when you retire. Nonsense. The interest will find you. I guarantee that if anyone stops working, lets it be known that they're not working and sits at home twiddling their thumbs. Within six months, the very outside, they will suddenly wonder how they ever managed to find time to go to work, because they would’ve had so many people ringing them up and saying, would you like to come and help with this? ..it never fails.”

She especially urged women to embrace the freedom of retirement and use it to pursue meaningful, fulfilling activities and follow their own personal interests.

People express amazement when you find older people doing anything with using their freedom.

"Isn't it amazing? You know, she's over 60 and there she is. She's doing a Massey unit. She's working in a computer firm. She's suddenly taken up whatever, adult education, embroidery, macrame, Latin, Greek law, whatever. There's nothing to stop her. It's only that we have been conned into believing that when you get older, you can't read and you can't learn, and you can't take in what you're reading about."

Those who were taught by Ida when she was an English teacher at New Plymouth’s Girls’ High School will recognise her commanding presence, quick wit, and clear views—qualities that left a lasting impression on generations of students.

Born in a steel mill town in Wales during the Depression, Ida’s early life was shaped by hardship. Her father, Edward Jacobs, was unemployed for much of her childhood.

A turning point in her life came when she won a full scholarship to the University of London—worth more than her father’s annual salary. There, she earned an honours degree in English and trained as a teacher.

After teaching in London throughout World War Two, Ida made the bold decision to emigrate to New Zealand, arriving on the RMS Rangitata in 1946. She met and married Victor Gaskin, and the couple settled in New Plymouth in 1961, raising five children. They later divorced.

Ida worked for New Plymouth Girl’s High School for 20 years and taught modules at New Plymouth Boy’s. She also held national leadership roles for the Post Primary Teacher’s Association.

Described as a lifelong Democratic Socialist, she became involved with politics, saying at the time she was interested in politics because she was interested in people. She stood as the Labour Party candidate for the New Plymouth electorate in 1984, which she only narrowly lost. She also served as a New Plymouth City councillor.

When Ida won the 1983 Mastermind it was the culmination of a lifelong love for Shakespeare that began when she started reading Shakespeare’s works, aged 10. She described the experience of being in the finals of the show as “traumatic” but her amazing memory and deep passion for Shakespeare meant she won the competition without even having to study for it, according to family.

The fame that came her way with the win of Mastermind was only one aspect to a life that was already remarkable.

Other accolades include being awarded a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit, for services to education and a honorary doctorate from the University of Waikato. She was the patron of the New Zealand’s Shakespeare Globe Centre and spoke every year at the national Shelia Winn Shakespeare Festival.

Ida was clearly an inspiring teacher, an academic, a community minded person with a fierce intelligence, with; “a mind like a steel trap” according to former student and former leader of the Labour Party and now incoming Wellington Mayor, Andrew Little. She was never going to let society’s stereotypes on the role of retired people restrict her and she urged others to do the same.

Ida died in New Plymouth in 2016. Her legacy is one of intellectual courage, community involvement, and a refusal to be limited by age.

Related Puke Ariki archives

ARC2004-1710 Oral History: Ida Gaskin, on her family and childhood in Wales (1984)

ARC2011-106 Oral History: Ida Gaskin discussing Welsh literature (2011)

ARC2011-105 Oral History: Ida Gaskin discusses Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (2011)

Related documents

Our Mastermind off to Britain Taranaki Daily News 16 August 1984

Honour for councillor Taranaki Daily News 5 November 1986

NP woman will head secondary teachers 29 April 1976

Please do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.