Amy Winterburn was born 1 December 1919 in Durham, Northen England, the eldest daughter of Willam and Selina Eddy.

Her father was a painter and decorator, and the family was large, she was one of 12 siblings. She described her home as a happy one filled with music, as her mother played the piano.

At the age of 14 she left school to help her mother at home, but then aged 16, against her parent’s wishes, went into service, working for a doctor’s family; which she said she really enjoyed; ”I’ve loved everything I’d done really”.

This kind of comment is often repeated in Amy’s oral history, which was recorded in 1993 when she was 73 at her home in Waitara - and makes up part of Puke Ariki’s oral history immigration collection. It reveals the remarkably positive attitude she brought to different roles and various challenges she faced during her life, growing up during World War Two, nursing, then life as a war bride and immigrant and mother and wife.

When World War Two broke out she left her job and decided to take up nursing, first in Leeds, then in Sheffield, which again she loved, despite constantly being required to shift wards and learn new specialities.

It was while nursing in Sheffield that she met her future husband, New Zealand serviceman Peter Winterburn, also known as Akapita.

Amy said a lot of teasing went on between nurses and the injured servicemen and that was how she and Peter first got acquainted.

“With Peter I remember taking a bowl of water to wash him in the morning and, just as he was already soaked, I took it away and, you know, teasing. We did a lot of that. And then one day, because I didn’t drink at all, and they were going up, some of the nurses and the patients, were going up to the pub at the top of the hill, and then I, oh, I wasn’t going to go. And you know, they said, oh, come along, you don’t have to drink, you don’t have to drink. So, I had a soft drink when I got there. And Peter dropped a ten shilling note out of his pocket and I picked it up and I said, ‘My golly, you need looking after’. He said, ‘I know I do,’ just like that you see.”

Amy was going on leave to stay with her parents but Peter; “Who wasn’t even a friend then, he was just one of the patients;” was stuck because the convalescent home he was meant to be going to was closed. On hearing this, Amy’s mother said, “oh, bring him home too.” And so, Amy did.

Amy’s parents both instantly took to Peter, due in part because they themselves had wanted to shift to New Zealand after WW1 but had been unable to, and because Peter was such a gentleman. After the trip home, Peter was “just one of the family, really”. He proposed to Amy not long afterwards.

She said the engagement was initially followed by shock and fear at the thought of having to move to New Zealand; “I thought, Oh No, what have I done?” It was her mother who reassured her that the marriage, and emigrating to New Zealand, was a good idea. Amy said she never once regretted her decision in the years that followed.

Amy and Peter were married in Durham in January of 1944 before he returned to New Zealand.

Peter, a member of the 27th Battalion, had sustained injuries in a battle near Tripoli, which were serious enough to end his war. Amy said the wound troubled him all his life, but he never once complained about it.

Amy sailed to New Zealand from Liverpool on the Port Phillip later the same year, apprehensive but excited, one of only four war brides aboard a ship of returning soldiers.

It was on her journey to New Zealand that she recalls first hearing the word, Māori being used, never having considered before this that Peter was Māori.

"And of course, Māori was never mentioned. I didn't even know anything about Māori. And it didn't worry me really, I suppose I’d never heard the word."

"But, he showed me photographs and I had a fair idea, but I never said a word about it. I didn't, I didn't want to hurt him anyway. Yeah, there was some mention, I think, on board ship about Māoris but it just goes over your head if you don't know."

Once she arrived in Auckland Peter took Amy all around the North Island meeting his family, including his mother who lived in Ōtaki. Peter’s father had died while he was serving overseas.

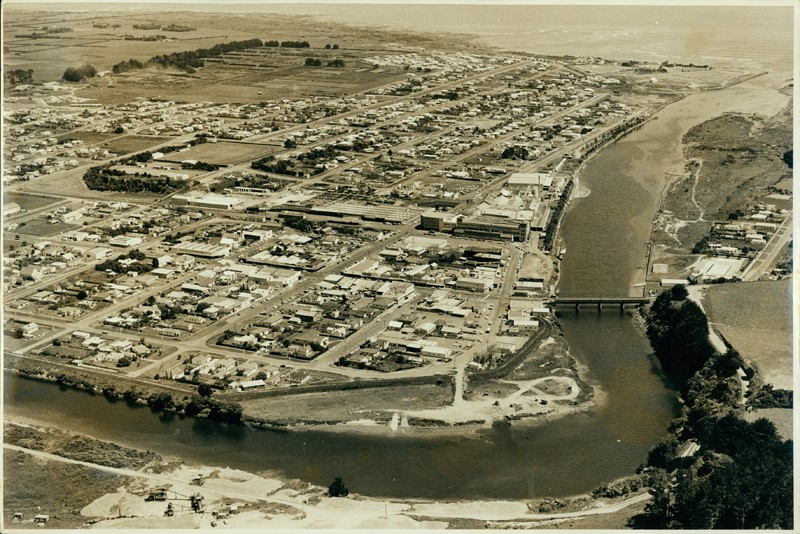

The couple eventually bought a hairdressing business on McLean St in Waitara, as Peter had learnt the trade as a schoolboy while working for his uncle.

The couple made Waitara their home for the rest of their lives and raised their three children there. Amy felt she and her husband were very welcome in Waitara but she was surprised at the racism she saw being directed at their friends and her husband (including children taunting him outside his own shop) and said she often felt confused and hurt that people could be so prejudiced - but tried not to let it upset her.

“Yes. Oh blow, I don't worry about people. I think if that's how they think, that's their ignorance.”

Peter died in 1980 after suffering from Alzheimer’s for many years and Amy died in New Plymouth on 16 October 2003.

Please do not reproduce these images without permission from Puke Ariki.

Contact us for more information or you can order images online here.